There has been a flurry of recent filings submitted to the Arizona Supreme Court related to Lake v. Hobbs—the case brought by Republican candidate Kari Lake to dispute the outcome of the 2022 gubernatorial election. Tracy Beanz recently did a complete breakdown of the filings and also gave an update on the Dark to Light podcast highlighting the Chain of Custody (CoC) issues.

Once again, a topic came up in the filings that has been at issue since the original trial in December 2022. Specifically, the issue of a signed affidavit submitted into evidence by the Kari Lake legal team from a whistleblower at Runbeck—the third-party contractor used by Maricopa County to help administer their elections.

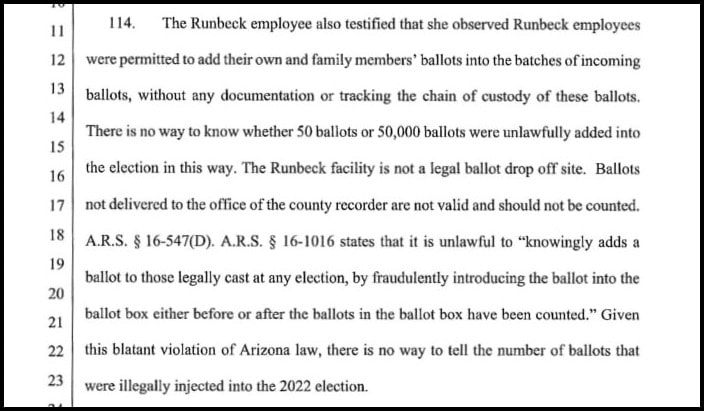

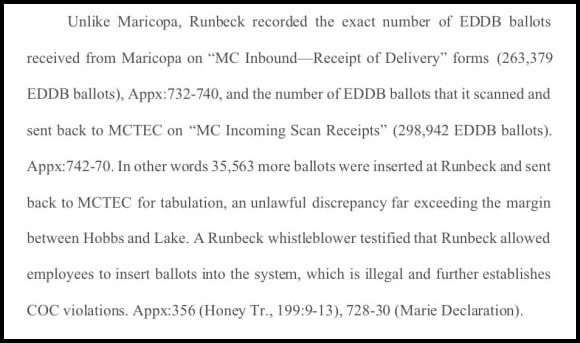

The whistleblower revealed that Runbeck was allowing employees to bring ballots from home—presumably their own or family members—and insert them into the official counts. She personally witnessed 50 ballots or more added to the counts. This would violate Arizona election law that only allows ballots to be delivered to polling locations, ballot drop boxes, election offices, or via the U.S. Postal Service.

This issue was brought up again in the brief filed by the Elias Law Group LLP—headed by Democratic super attorney Marc Elias of Steele Dossier fame—on behalf of Katie Hobbs. We thought it might be helpful to go a little more in-depth about how the Elias Group continues mischaracterizing the evidence and is exploiting the lack of understanding to mislead the public.

Adam Carter briefly mentioned the deceptive tactic during livestream coverage on Day 1 of the trial—alongside Tracy Beanz.

As mentioned in the video segment, Carter is an accountant with experience working for one of the “Big 4” accounting firms. During his time there, he worked in external audit—including working on audit engagements for Fortune 500 companies.

Now, we understand auditing corporations is not exactly the same as auditing an election, but the differences are really insignificant in explaining these concepts. For this column, we are going to speak in terms of auditing a publicly traded company. The methodology is—for the most part—the same and will give a better illustration to the reader of the concepts being discussed. Just know the process and methods being explained are transferable between the two.

A company prepares financial statements that must be audited before they can be issued publicly to the markets for investors to make decisions based on them. For obvious reasons, companies are motivated to overstate parts of their financial statements—such as sales revenues or assets—to drive up their stock price, qualify for better loan terms, etc. So no experienced investor will rely on financial statements that an independent third party has not audited. When conducting an audit, there are two forms of testing conducted; Substantive testing and Controls testing.

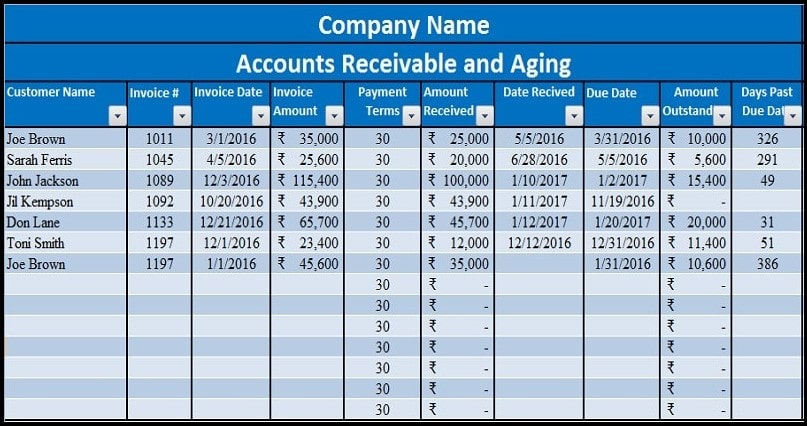

Let us take Accounts Receivable (A/R) as an example. Most companies provide goods or services and then bill their customers to be paid later. These unpaid bills are listed on the company’s balance sheet as an asset (i.e., money the company has already earned, is entitled to, and expects to collect).

Substantive testing is exactly what would come to mind when a layperson thinks about an audit. A company reports the amount of A/R on its balance sheet. To substantively audit, an audit firm would request a detailed listing of all transactions that comprise the balance of the general ledger account(s). The auditors would then select a representative sample of the entire population and request supporting documentation for each transaction chosen (invoices, purchase orders, shipping documents, etc.). As long as the company can provide the documents—and no problems are found when examined—then the auditors can give assurance the account balance(s) are reasonably stated.

This now brings us to Controls testing. Financial controls have been a concept in accounting and auditing for a long time. However, renewed importance was given in response to the Enron & WorldCom accounting scandals of the early 2000s. In the wake of the scandals—and subsequent financial meltdown—Congress passed The Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX).

*Interesting Sidenote: As Julie Kelly and Glenn Greenwald explain in the video above, the primary felony charge being weaponized by the U.S. Dept. of Justice (DOJ) against Jan 6th defendants—18 USC § 1512(c)(2) – Obstruction of an Official Proceeding—was passed as part of the SOX Act. The statute has no application to political protests, and these defendants are, effectively, being charged with breaking accounting laws.

SOX put into place two major requirements for the Chief Executive Officers (CEO) and Chief Financial Officers (CFO) of all publicly traded companies subject to its regulations. Both the CEO and CFO are required to sign statements attesting:

A. Financial statements were “fairly present in all material respects the financial condition and results of operations” and “does not contain any untrue statement of a material fact or omit to state a material fact … [are] not misleading”.

– and –

B. “Responsible for establishing and maintaining Internal Controls. Have designed such internal controls to ensure that material information … is made known … and have presented in the report their conclusions about the effectiveness of their internal controls.”

Adding the statement about internal (financial) controls was the major change, and knowingly signing either statement falsely can carry a 20-year prison sentence. Needless to say, company executives and audit firms both take the requirements very seriously.

It was no longer good enough for company executives to sign off that financial statements had been prepared accurately to the best of their knowledge. Those tasked with corporate governance now had to attest they had an internal controls framework in place to prevent material misstatements from impacting their reported financial results.

Believe it or not, most financial report misstatements are not the result of fraud (i.e., intentional). When looking at one of the mega-corporations—Walmart, for example—they are conducting business transactions at such scale and volume, it would be impossible for top executives to know what is happening down in the details of the accounting ledger. And it is not uncommon at all for significant accounting mistakes to occur and compound over time. Therefore, corporations now have to implement a robust framework of internal controls designed to both prevent and detect potential financial misstatements.

Auditors, likewise, cannot effectively substantively test all these transactions. Just think about how many sales, deliveries, purchase orders, billings, and returns Walmart engages in every hour of every day. How are you supposed to test all of that? There are not enough auditors in the world.

Audit firms, therefore, have to rely heavily on the controls put in place by the companies when conducting an audit. For larger audit engagements, accounting firms usually keep auditors on-site at the client locations year-round. Doing what you ask? Controls testing.

How To Do Controls Testing

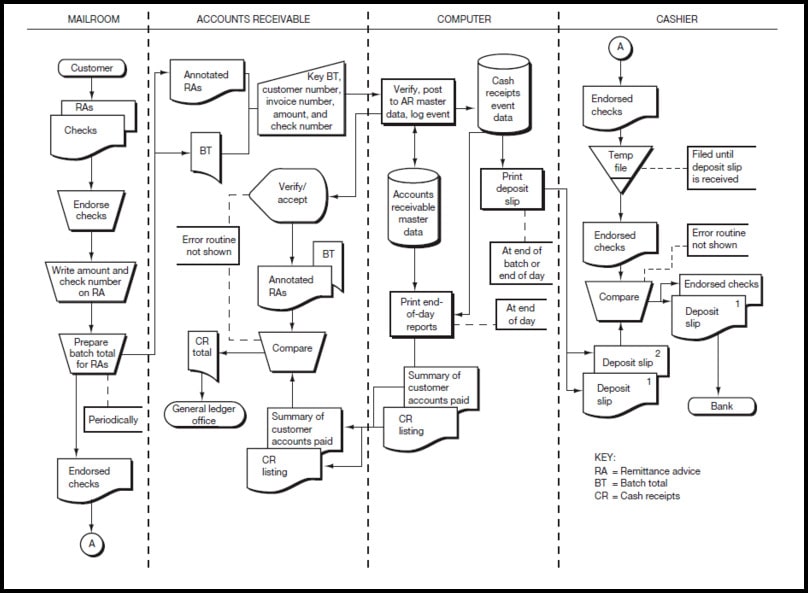

In order to test the financial controls, auditors will first obtain a narrative of the accounting procedures for all relevant areas and document their understanding of the processes and controls—including generating detailed flowcharts. The independent auditors then evaluate the design of the controls to form their own opinion if the controls—even if operating correctly—will, in fact, detect and prevent financial misstatements.

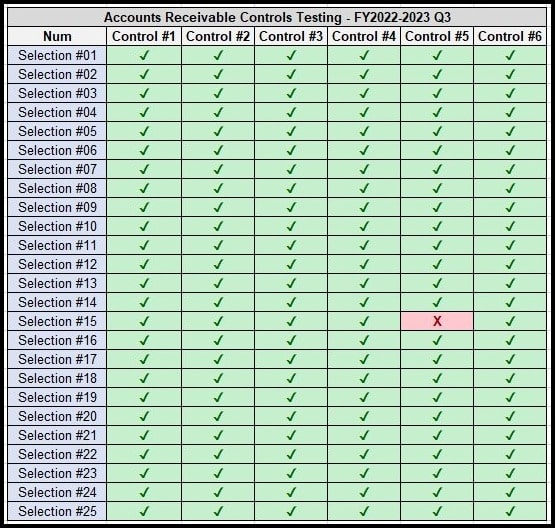

Once the process is documented and evaluated, the auditors will identify all the key controls in the process to test. And as with substantive testing, the auditors will request a complete population of the entire period being tested to make selections. In my experience, auditors typically select 25 transactions to test regardless of the size of the population and request supporting documentation (ex., customer credit approvals, properly accepted purchase orders, invoices issued with evidence of review and approval, etc.).

Why 25 transactions and not vary based on population size as with substantive testing? Because the goal is not to test if the overall account balances, the goal is to test if the controls are operating effectively, and typically testing 25 transactions will highlight if widespread control failures are occurring. It is a simple Pass/Fail test. Either the steps in the control were properly executed, or they were not.

If no issues are found with the selections, the auditors can determine the controls are operating effectively and can be relied upon when issuing the eventual audit opinion. If failures are detected, the auditors will take steps to determine how pervasive the control failure(s) are. This could include making additional testing selections (typically 15 more) to see if other control failures are present or if the prior failure was simply an isolated (one-off) occurrence that just happened to get picked up in the selection. Hence they will audit more.

If failures are determined to be widespread, auditors may perform procedures to determine if secondary controls would help mitigate any potential for financial misstatement. But if the problems appear systemic—and the controls can not be relied upon—the audit firm will report the company has a material weakness in its financial controls structure and switch to fully substantive audit procedures.

How Does This Apply To The Kari Lake Case?

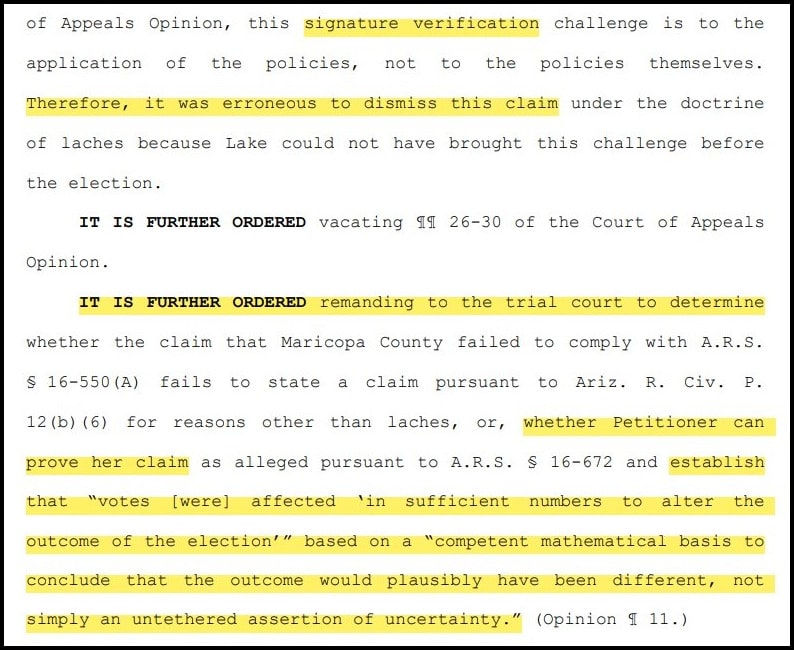

The big headline of the Arizona Supreme Court’s decision in March was the reversal of the trial court’s ruling not to allow Kari Lake’s challenge whether Maricopa County followed signature verification procedures. The judge dismissed the claim based on the legal doctrine of “Laches”—which, in and of itself, is absurd—as explained by attorney Robert Barnes and Alexander Mercouris on a livestream of The Duran.

Laches has no applicability to election law.

What went largely unnoticed, however, was the Arizona Supreme Court went on to overrule the trial judge on his determinations that Lake needed to prove the outcome of the election would have been different based on a “competent mathematical basis … not simply an untethered assertion of uncertainty.”

That has never been the legal standard in election law at-large. Candidates are not required to conclusively, mathematically prove the election outcome would have been different—an almost impossible legal standard to achieve. Traditionally, candidates only need to prove the election outcome is sufficiently in doubt.

Yet—in the original Lake v. Hobbs decision—the trial judge dismissed Lake’s arguments point-by-point, claiming she may have proven her individual claims of election maladministration, but none of her claims mathematically prove the election outcome would have been different.

That’s where this “50 ballots” issue comes into play. Lake’s attorneys never presented it as a substantive numbers argument that would alone overturn the margin of victory. It was presented to demonstrate Runbeck had a Controls failure in their processes. In fact, they were alleging Runbeck was ignoring Arizona election law in the regular course of their operations. And due to Maricopa’s lack of CoC documentation, they had no means to prevent, detect, or mitigate the Controls failures occurring at Runbeck.

Couple this with the 35,563 ballot discrepancy in Maricopa’s trial exhibits, where they cannot reconcile the number of ballots sent to or returned from Runbeck. There is no way to know if it is 50 ballots, 35K, or even more illegally injected into the vote count. And given the total margin of victory was approximately 17,000 votes, that would certainly cast the election’s outcome in doubt.

“Specifically, the math surrounding the “unaccounted-for” ballots refers to evidence presented in Lake’s Mar 1st, 2023, appeal to the Arizona supreme court. Lake’s team showed Runbeck recorded 263,379 inbound ballots and sent back to MCTEC 298,942—a difference of 35,563 ballots. Hobbs won by a tight margin— approximately 17,000 votes.” ~From the UncoverDC article ‘Kari Lake Asks Court to Reconsider Maricopa County’s Chain of Custody Issue‘

Yet, attorneys for the Elias Law Group have harped away (paraphrasing), “They only allege 50 ballots” to straw man Lake’s argument and mislead the public. And the trial judge, sadly, latched onto it to justify his decision. The Arizona Supreme Court rightfully called them out on it.

In closing, the importance of the decision the Arizona Supreme Court already made in the Kari Lake election contest cannot be overstated. As Robert Barnes explained in a recent livestream with Viva Frei:

“So credit to Kari Lake for pursuing it because doing so was the best case, the best win legally for election integrity in decades.” ~ Robert Barnes